Sleep of the Just (The Sandman #1, Preludes & Nocturnes)

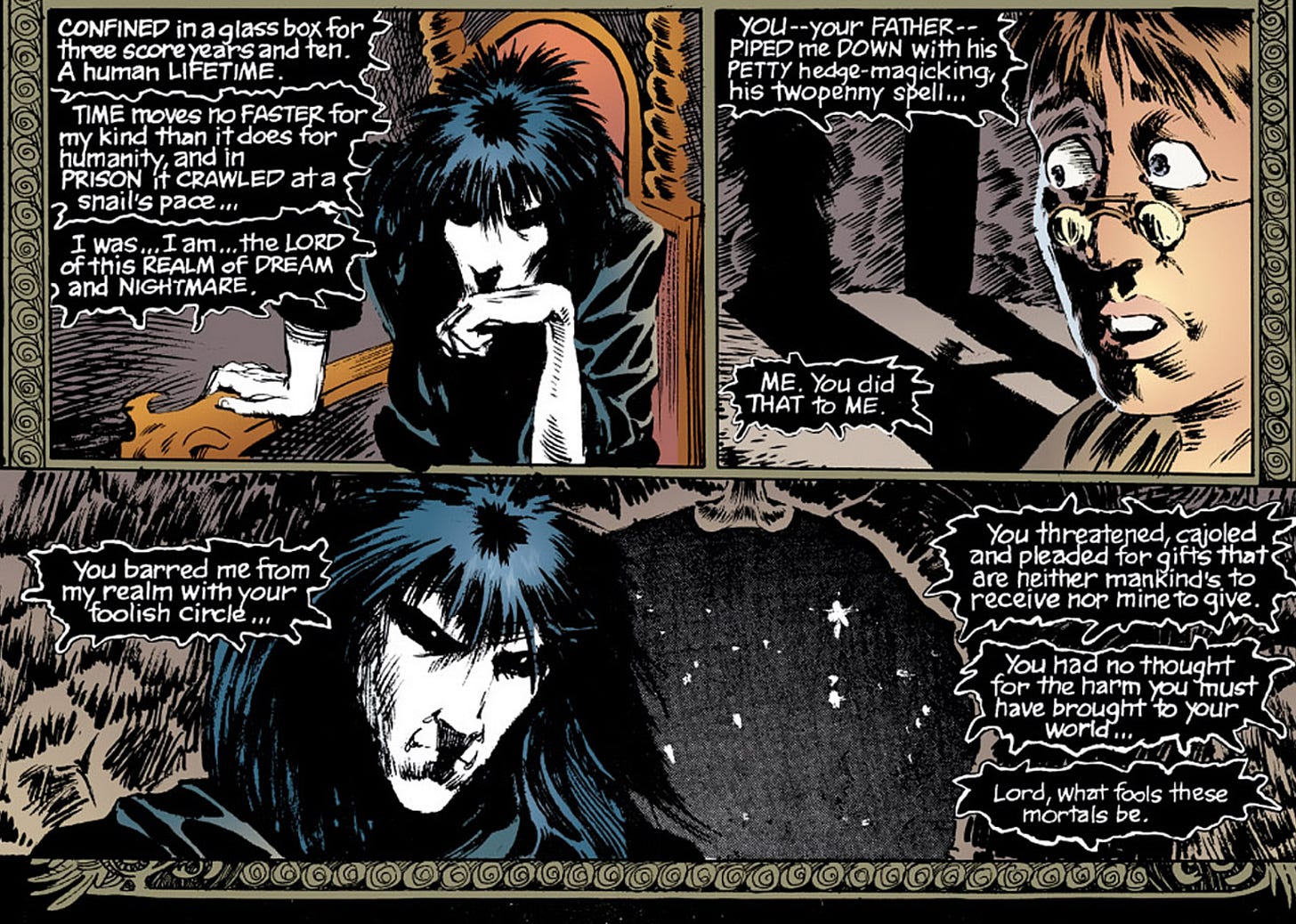

"You threatened, cajoled and pleaded for gifts that are neither mankind's to receive nor mine to give. You had no thought for the harm you must have brought to your world."

Hello, Dreamers!

Welcome to the first issue of “Shadow Truths”, where we will explore the world of The Sandman by Neil Gaiman, one of the most acclaimed and influential comic book series of all time. It has won numerous awards and accolades, such as the World Fantasy Award for Best Short Story in 1991 (the first comic book issue to win in a literature category, and also the last one, but that’s a different story), several Eisner Awards for Best Writer and Best Continuing Series, and a place on The New York Times Best Seller list.

The Sandman has also been adapted into various media formats, such as Audible-exclusive audiobooks and a Netflix series by the same name.

I will be pulling from all of these if and where necessary, but mostly, this newsletter will be based around the original comics. If you feel inclined to read along (and I recommend it, although it’s not a must): I already briefly went into the different editions available in this post—there is something for every preference and budget. So let’s go…

In this issue, we will focus on “Sleep of the Just", which introduces us to the main character, Dream of the Endless, also known as Morpheus, the King of Dreams and Nightmares. I will start each newsletter with a little synopsis…

The story begins in 1916, when a group of occultists led by Roderick Burgess attempt to summon and capture Death (Dream’s older sister), in order to gain immortality and power. However, they make a mistake and trap Dream instead, leaving him imprisoned in a glass globe (lovingly called “the fishbowl” by most fans) for decades. It is interesting to mention that the glass cage (obviously, glass is mostly made from sand) imprisons his body while a binding circle prevents him from making use of his powers e.g. inducing sleep and making people dream.

Meanwhile, in the real world, people are affected by Dream's absence in different ways:

There is the impact of Dream not being able to attend to his function, which causes the “sleepy sickness”, or Encephalitis Lethargica (a wonderful connection of fantasy and reality since there really was a wave of Encephalitis Lethargica at the time). We meet Unity Kincaid, a young woman who sleeps through most of her life, and whose story stays interwoven with Dream’s for several issues to come.

But there are also those who are more directly impacted by Dream’s captivity, like Alex Burgess, the son of Roderick, who inherits his father's obsession with keeping Dream captive.

Finally, after over 70 years of captivity (which have been stretched to over 100 for the TV series to bring it to the present day), Dream finds a way to break free from his glass cage. He takes revenge on his captors and sets out to recover the vestments that have been taken from him:

There is the pouch of sand. The sand never runs out and is endless (ha, see what I did there?), can put anyone to sleep and induce dreaming. It can wreak havoc in the wrong hands (we learn about its addictive properties later on). Dream also uses the sand to transport himself and others between realms.

Dream's helm looks a bit like a gas-mask (which is a nod to DC’s Golden Age Sandman Wesley Dodds, but I won’t go into that connection too much here), and has been crafted by Dream himself from the skull and spine of a dead god that he once defeated. He wears it for both protection and as a symbol of office/his authority and power, especially when making visits to other realms and planes of existence. We’ll definitely learn more about that later on. It is also his sigil among his other Endless siblings.

The ruby is a dreamstone that contains most of Dream’s essence. It allows him, or whoever wields it, to manifest dreams, bring dreams into reality, and even reshape reality itself. It can also be used to manipulate people by changing their hopes and dreams. Again, we will learn much more about it in later story lines. Think of the ruby as a kind of computer (oh, I’m awful) that automates things for Dream.

"Sleep of the Just" is a brilliant introduction to the complex and fascinating mythology of The Sandman. It establishes the tone, the style and the themes that will be explored throughout the series. It also showcases the art of Sam Kieth and Mike Dringenberg, who create a dark and surreal atmosphere that perfectly matches Gaiman's vision (I have to say though that especially Sam Kieth’s art isn’t my favourite. I personally could never warn up to it, and I think it is indeed harder to warm up to if you aren’t used to reading comics—that just as a word of warning to those of you who are new to the medium).

The Pain Points

Let’s start with the obvious (we’ll get to the slightly more subtle and obscure in a minute):

A Tale of Confinement, Trauma and Oppression

“Sleep of the Just” is, above all, a tale of confinement. Confinement of hopes and Dream/s. All its main protagonists are prisoners in one way or another, and for some, there is no escaping that prison. And even those who do are forever scarred (I would love to use “changed” because it’s true, but it is such a loaded word in this context, right Sandman fans?).

More specifically, Dream’s story arc, not just in issue 1, is one of trauma. At this point, we’ll only look at the trauma experienced in “Sleep of the Just”, and that is first and foremost the trauma of his imprisonment, which we can take both literally and metaphorically: Isolation, powerlessness and humiliation (he spends the entirety of his captivity naked). Initially, that leads to stoic silence, unwillingness to strike a bargain (bravo!) and cold vengefulness (perhaps not quite so bravo).

However, if one knows the story in its entirety, one will also know that these are traits that were already inherent to Dream’s personality, at least to a degree. When we first meet him, he is lawful neutral at best (if you wanted to talk in Dungeons & Dragons alignments).

Nevertheless, his trauma is also a catalyst for change, as we will learn later on. Or do we? And is it?

One big difference between the Netflix TV series and the comics is that Roderick and Alex Burgess have both been graced with a backstory and a bit more dimensionality. They aren’t just your stereotypical villains like in the comics.

Roderick Burgess suffers from feelings of grief and guilt because he lost his oldest son in World War I (it is the reason he wants to capture Death—he wants to strike a bargain to get back his son). However, he also has very obvious delusions of grandeur and abuses his son Alex both emotionally and physically.

Alex Burgess is trapped by his father's legacy and fears. He suffers from low self-esteem, anxiety, and potentially depression. There is an element of sympathy for Dream’s plight—it is probably not wrong to assume that he sees him as a fellow prisoner.

And yes, all of this also makes “Sleep of the Just” a tale of oppression. Roderick Burgess denies both Dream and Alex freedom and dignity. He also tortures both (physically, mentally, or both), and the consequences are far-reaching since they affect the victims’ sense of belonging, safety, and empowerment.

Speaking of Dream not being quite so nice though: Especially in the TV series, we see a wonderful (?) display of “Revenge Before Reason” at play several times: Alex would have released Dream for an assurance to spare his life, but Dream is too proud and cannot forgive him for having killed his raven Jessamy.

Yes, that’s who Dream is at this stage: Proud and vengeful. After his escape, he gives Alex the “gift” of eternal waking (or sleep in the TV series): He essentially traps him in a never-ending nightmare, tormented by fear and dread.

The Weight of Conscience

We can interpret the gift of eternal waking as a metaphor for the connection between our conscience and our mental health: Experiencing insomnia, depression and anxiety because of our actions or inactions are probably something we all can relate to. But even more importantly, it shows how we lose our connection to imagination, emotions and our sense of wonder. And this is something that is also quite aptly seen (metaphorically) in all the people who suffer from the sleepy sickness during Dream’s captivity:

They are either trapped in their dreams or unable to dream, and we all know that this has to impact mental health. They lose their sense of identity, purpose, and joy. It is not unlike what we experience in the depths of depression, when we either feel nothing, or when we begin to use dreaming and fantasising as an escape.

Stories and Narratives

Dreams can be a powerful source of healing, but also of dissociation, trauma and pain. They reflect our inner conflicts and desires (more about that another time), which obviously raises questions about the nature and purpose of dreams:

Are they just random images and sensations that our brain produces while we sleep, or are they something more?

Do they have a meaning and a message for us?

And what happens when we lose or manipulate them?

The bottom line seems to be that dreams (both while we are sleeping and while we are awake) are an essential part of our humanity, and without them or too much of them, we become empty shells or monsters.

Escapism, Detachment and Dissociation

I mentioned Dream’s symbols of office earlier. As the Lord of Dreams, he possesses a set of vestments that symbolise his power and authority, and these vestments are not only tools for his duties. They also metaphorically reflect his mental state and creativity:

The helm is a protection of sorts, and it can also serve to put fear into whoever should be afraid (at least in Dream’s opinion). But it also represents his detachment from his emotions and his rigid adherence to his role. One could say that he wears it to hide his true face (and feelings) from others, and to assert his dominance over his domain. However, this particular mindset also also makes him cold, aloof and lonely.

The pouch of sand represents creativity and inspiration. Dream uses it to create stories, images and symbols that enrich (well, usually) the lives of dreamers. But the dream sand isn’t entirely benign: If it falls into the wrong hands, it has addictive potential, as we will learn at a later stage. It symbolises, once more, the ambivalence of dreams: Dream too much or too little, and you will lose your equilibrium.

The Weight of Responsibility

The ruby contains a large portion of Dream's essence. It represents the entirety of his powers and responsibilities. He created it to help him perform his duties more efficiently, but he also poured too much of himself into it, making him somewhat dependent on it. When the ruby falls into the hands of mortals, it causes chaos and destruction.

All of Dream's vestments show how he relates to himself, others and his role as the Lord of Dreams. They reflect his strengths and weaknesses, his joys and sorrows, his growth and change, and this is something that stays important throughout the whole story arc.

The Exploration

Since I am continuously skirting the lines between being a psychotherapist, a creative artist and a writer, I would like to give you a few questions to ponder that relate to mental health and creativity and have a direct or metaphorical connection to “Sleep of the Just”.

What role do hopes and dreams play for your well-being, and what happens when they are confined?

Dreams, in both the literal and metaphorical sense, are not only a way of processing our experiences and emotions, but also a source of inspiration and insight. They can help us cope with trauma, express ourselves, and discover new possibilities. Dreams are vital for our mental health, and it is damaging when we are deprived of them.

How do you relate to stories and imagination?

The Sandman, as a whole, is about stories, and how they shape our own narratives and hence our lives. Stories are another way of exploring our inner world and expressing our creativity. They can help us understand ourselves and others better, challenge our assumptions, and inspire us to change. When Dream is captured, his realm (the Dreaming) begins to fall apart (also a powerful metaphor for trauma btw). This shows how powerful stories are for our mental well-being, and how important it is to preserve and nurture them. Did you ever try to write your own?

How do dreams/stories and reality intersect for you?

Where do you personally draw the line between processing, using story/dreaming creatively, and using it as an escape?

What narratives currently affect your reality?

Who created them (pay particular attention to the ones you created yourself)? And is that influence a positive or a negative one?

Do you think it is possible to change and reframe narratives you hold on to for achieving a different outcome?

If you do: Where would you start? If you don’t: Why is that?

What is your relationship with discomfort?

Do you tackle it head on, or do you have a tendency to detach from it? Can you find pros and cons for both?

That's all for today. I hope you enjoyed reading as much as I loved writing. If you have any questions or thoughts, or would like to share what you found out when you explored above questions, feel free to leave them in the comments, or join our chat.

If you liked this post, please subscribe and share it with your friends who might be interested in The Sandman, too.

Stay tuned for the next issue, where we will discuss #2: “Imperfect Hosts”

Until then, sweet dreams! 😉